|

Startseite

© 2019 Dr. Graumann-Brunt |

|||

Sea squirts and the question: Do we need a nervous system and a brain if we lead an exclusively sedentary life? © Dr.Sigrid Graumann-Brunt Sea squirts are VIPs, but not because of their unquestionable beauty; their claim to fame is that they are particularly uncompromising advocates of sustainability in the manner in which they dispose of their own resources.

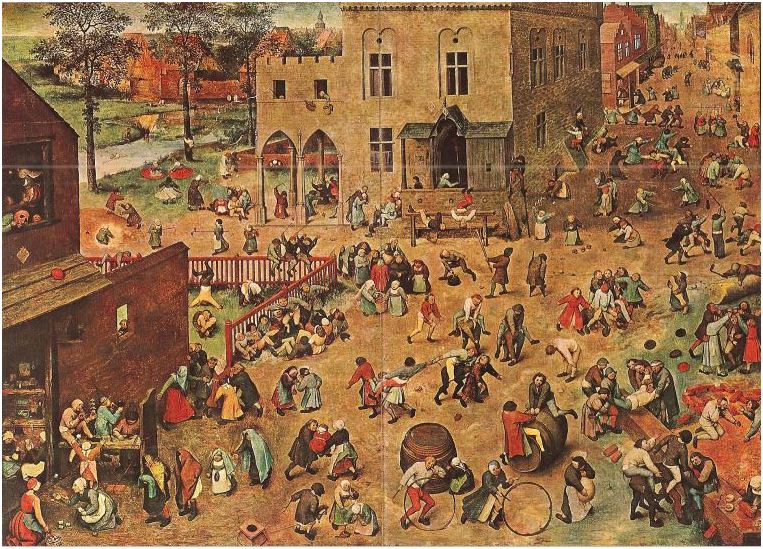

These pictures were taken from Goodheart's Extreme Science https://goodheartextremescience.wordpress.com/?s= “Is it really true that they eat their own brains?“, someone asks in a blog. Yes, it is evidently true. They do indeed. And they begin to do so from the moment they resolve to settle permanently in one place, quite content to simply wait for and devour any prey that swims their way. They cease going in search of food and henceforth stay in one and the same place. These observations raised the question as to whether a permanently sedentary lifestyle that coincides with a degeneration or renunciation of a nervous system, as it does in the later stages of the sea squirt´s life, might not necessarily be confined to these creatures alone; but could be a phenomenon with implications of a more general nature? This line of inquiry was pursued, and various authors have put forward findings that all point in the same direction. Reference is usually made at the outset to the fact that sea squirts are vertebrates, which makes them relatives, albeit distant ones, of ourselves, a fact that would allow us to draw parallels (the octopus is apparently different; see the very interesting comment made at the end of Llinas´s highly recommendable book “I of the vortex: From neurons to self“). In texts on functional neurology we find consideration of the nature of goal-directed self-induced movement in an environment. Voluntary movements always have a direction; this is perfectly logical and natural. The direction needs to be defined in advance when determining the objective. This in turn necessitates an appropriate plan and requires the readiness of a series of individual impulses coordinated to form a meaningful whole. On the surface, of course, these are motor impulses, but the impacting influence of other systems, sensory, endocrine, vegetative, emotional and the experience factor must also be borne in mind. The time line also plays a part, with plans being forged in the present for an event that is to take place at a point in time in the future. The conclusion to be drawn from this is that, as far as the sea squirt is concerned, movement and the development of a nervous system, a brain, are so closely interconnected that the onset of the recycling process, once the creature has taken up its permanent inert state, seems to be perfectly logical. Can any conclusions really be drawn from these considerations in respect of our own lives as human beings? The science of functional neurology says one can. It is here that we find reference to the development of movement and a link to that of thought processes. In fact it goes a step further by pointing to evidence that could lead us to believe that thought processes make use of FAPs, patterns with their origin in movement. However, there are many implications that need to be considered. It is by no means a simple straightforward matter. It goes without saying that reaching out (fine motor skills) to grasp an object requires a plan, even more so when the object needs to be handled, but this does not constitute any actual movement of the body; there is no relocation to another place and therefore no accompanying view of the environment from a different perspective. One thus finds oneself having to distinguish between goal-directed movement involving a change of location and such involving none, and fine versus gross motor skills. It also raises a lot of other questions. It complicates matters even further when one begins to look at the nature of the innate (not consciously performed) patterns of movement in early infancy from this perspective. The movements of the foetus most certainly follow a pattern (without the body relocating to another place), but what about the non-directional movements or the baby kicking its legs and waving its arms about? But one thing is for sure: movement plays a very important role. It has been known for quite some time that movement is beneficial to sufferers of both physical and mental health conditions. But it is equally important to remember, particularly where dealing with children is concerned, that movement supports thought processes. This doesn´t just mean sporting activities, it includes much more than this, as Bruegel´s painting of children at play clearly shows. Whether it is symbolic play, games with dice or sporting contests, all the children in the picture are in motion. Even primitive patterns of movement can be seen: a boy sitting in the garden has taken up a bending position (with eyes closed as far one can tell).

As already said, this line of inquiry provides much food for thought and discussion. One such question would be to investigate whether connections may be found between specific aspects of movement development, the initiation of autonomous planning and peculiarities in the process of developing thoughts and ideas. It is not only just recently that reference has been made to a connection between movement and the development of powers of thought. Piaget also recognized that the roots from which the process of thinking grew and developed were to be found in movement. In education theory in Germany in the thirties there were numerous approaches that pointed in this direction: for example the holistic approach advocated by Johannes Wittmann, who had the children moving about in groups as a way to developing their notion of numbers. And even much earlier than that, it was Gottfried Keller who, in a short story, pointed out that a connection between movement and thought can also be seen to function in the opposite direction, i.e. that movement can be enhanced by thinking. Deploying thought to this end is a theme in his story “Das Fähnlein der sieben Aufrechten“ (engl.“The Banner of the Upright Seven“). Karl, the hero of the story, has to learn to shoot with a gun at all costs if he is to win his beloved Hermine. His father, however, is not willing to provide the financial means needed for him to practise; firstly the Swiss are thrifty as a matter of principle, and secondly he and his friend, Hermine´s father, have pledged not to jeopardize their friendship by allowing their children to marry one another. The following scene ensues (quotation): …...But he (his father) came at just the right moment; having previously missed the target half a dozen times, Karl now fired a series of rather good shots. “You can´t fool me that you´ve never done any shooting before; you´ve no doubt spent many a franc behind my back. Of that I´m quite sure!“... “Well, I have been practising secretly, but it hasn´t cost anything. Do you know where, father?“ “I thought as much!“ “I often used to watch the shooting as a boy, taking in all that was said, and I´d been yearning to do it for so long that I was even dreaming about it; I lay in bed, in control of my rifle for hours on end in my mind´s eye and firing hundreds of well-aimed shots at the target.“ “Well, that´s splendid, that is! In future they´ll just have to consign entire rifle companies to bed and order them to do some mental shooting practice. That´ll save gunpowder and boots!“ “It´s not as silly as it sounds“, said the experienced marksman who taught Karl.“You can be sure that of two marksmen with an equally good eye and of equally steady hand, the one accustomed to thinking will end up champion......“ Karl of course goes on to win the silver goblet he has so yearned for and his beloved Hermine by virtue of his shooting prowess. We learn from Keller that remaining still in one position in no way points to the absence of a brain. His protagonist is able to make good use of his while simply lying there motionless. One mustn´t forget, however, that Karl has an aim and plans (forming in his mind), which are directed at movement: he wants to win Hermine´s heart. But this in turn brings us back to the sea squirts; what they do while swimming around is very much the same: they are looking for a mate; once this is achieved, they do not appear to be in any further need of a nervous system or a brain. Unfortunately, we do not know what later becomes of Karl. |